And then came the Blitz

Researcher Stefano Paolini has a passion for history, particularly WW2 and the events surrounding Britain’s internment of Italian Enemy Aliens. A British-born Italian with firm roots in London, Stefano has collected a wealth of witness accounts referencing the events of 1939-1940 and what culminated in Churchill’s infamous order of ‘Collar the Lot’.

We met up with Stefano Paolini to ask him a few questions regarding his research into the events leading up to one of the less known human tragedies of WW2 - the sinking of the SS “Arandora Star”.

What is your manuscript about?

The manuscript is about the internment of Italians resident in Great Britain during the Second World War. It focuses upon the impact internment had on their lives between 10 June 1940, when Italy declared war on Great Britain and France, and 02 July 1940, when the SS "Arandora Star" carrying German, Austrian and Italian internees to internment camps in Canada was torpedoed in the Atlantic Ocean by a German U-boat and sunk off the Irish coast. Over 850 people lost their lives, 446 were Italians.

What is ‘internment’?

Internment is the detention or confinement of foreign or enemy nationals during wartime. In practice it is the arrest without charge and the detention without trial of an individual who has an allegiance to a foreign government. The common law assumption that an individual is innocent until proven guilty is turned on its head with the individual having to prove their innocence first.

What can you tell us about the Italians in Britain at the time?

By 1940 there were around 18,000 Italian nationals living and working in Great Britain. They had poor formal education and were employed as caterers working in cafes, restaurants, temperance bars, fish and chip shops, ice cream parlors and provision shops. They were usually family run businesses employing relatives from their extended families. There were also Italians working as ice merchants and knife grinders. Some worked in the terrazzo laying industry and a few as teachers and musicians.

Where in Italy did the migrants come from and where in the UK did they settle?

The generation of migrants in 1940 came mainly from mountain villages of Northern and central Italy. The majority settled in London where Italian migrants as far back as the early middle of the nineteenth century established the first ‘Little Italy’ in Clarkenwell, EC1. From here Italian families began to spread out of London and venture west into Wales and north to Manchester then into Scotland. By 1940, Italians could be found all over Great Britain in cities, towns and hamlets, visible in their communities due to their catering connection on the high street. Italians integrated well into British society.

What did Fascism mean to Italians in Britain?

In 1922 Benito Mussolini became Italy’s Fascist dictator. He wanted to export his politics to Italian migrants, including those living in Great Britain. This was achieved by opening Fascist clubs, where Italians could socialize together. In 1922 the first opened in London and by 1940 there were Fascist clubs in Cardiff, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh. There were many benefits to be had by joining the party such as subsidized holidays to Italy for the children of Italians, education and social events. It was the first time an Italian government took an interest in the welfare of its emigrants and many joined for patriotic rather than political reasons. Fascism was born in Italy but so too was anti fascism with Italians resident in Britain campaigning against Fascism. Many Italians were apolitical whose lives were religious rather than political.

How did the outbreak of The Second World War affect these communities?

At the start of the war between Britain and Germany in September 1939, the British government introduced policies to protect the civilian population. Italian residents followed these government policies by sending their children away to less built-up areas, usually in the countryside, observed blackouts, rationing, and sent their British born children to serve in the British armed forces. In essence, they were faced with the same difficulties as their British neighbours.

How did the war Cabinet view Italians resident in Britain?

Around 70,000 German, Austrian and Czechoslovakian aliens (the definition given by war cabinet) entered Great Britain between September 1939 and June 1940. The vast majority were refugees escaping persecution in their own country. However, the British government was concerned that amongst genuine cases, the Germans would try to send spies to sabotage British defenses. Chamberlain’s war cabinet countered the threat by assessing individuals with a tribunal. Unlike German nationals, resident Italians were not required to go to tribunals because Italy was not at war with Britain but they did have to register with their local police. In the meantime, MI5 made a list of Italian men who would be immediately interned if Italy entered the war against Britain. These were the 1500 members of the Fascist organizations based in Britain, defined as ‘dangerous characters’. They were regarded by MI5 in the same way as the interned Germans (grade ‘A’), even though many of the alleged ‘dangerous characters’ had sons serving in the British armed forces, and some families had lived in Britain for more than 40 years.

What happened on 10 June 1940?

At 4.45pm Benito Mussolini declared war on Britain and France. It was the news that Italians in Britain had feared the most. Immediately after the declaration, vandalism against Italian property began. Shops were smashed and looted although violence against individuals was rare. Churchill gave the order to ‘collar the lot’. This meant that along with the 1500 ‘dangerous characters’, all Italian men resident in Britain would be interned.

What did ‘collar the lot’ mean to Italians?

Italians who had just witnessed the destruction of their property and had called police for assistance, to their dismay, were arrested and taken away. Some of the officers had the embarrassing task of arresting men who had been in the area all their lives. Many arrests were carried out in darkness enforced by the black out and in the presence of children. Churchill’s order to ‘collar the lot’ meant that in two weeks around 4100 men had been arrested throughout Great Britain, 400 were British born.

Where were the internees taken?

Initially, they were taken to local police stations, but later transferred to larger ‘aliens collecting stations’. These were hastily improvised camps (horse racing tracks were also used), surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. In some cases, Italian ‘enemy aliens’ were guarded by their British born sons, serving in the British armed forces. Internees were allowed to send and receive mail but letters and packages were censored and rarely made it to their recipients. The movement of internees from camp to camp was swift, but their records were often inaccurate. The most infamous camp was a disused cotton factory at Wharf Mills in Bury near Manchester.

Did the internees remain at Wharf Mills?

The Italian internees spent around two weeks at Wharf Mills. They were destined for indefinite internment in camps on the Isle of Man, Canada and Australia. On 17 June 1940 a conference was held at the War Office to discuss the movement of Prisoners of War and Internees to Canada. The 1500 members of the Fascist organisations in Great Britain would be deported on several ships to internment camps in Canada. One of these ships was the SS “Arandora Star”

Tragedy

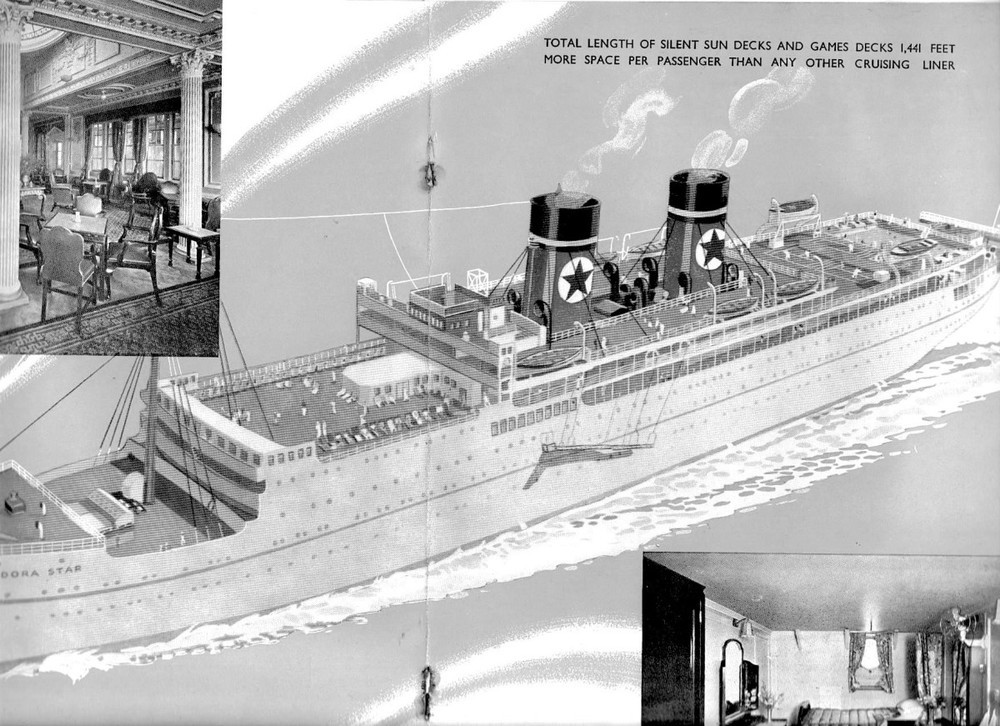

Before WWII erupted, The Arandora Star had been a luxury cruise liner. She carried 354 first class passengers to the Mediterranean and the Norwegian Fjords. Her white exterior, and the many ribbons adorning her masts, gave her the nickname of “The Wedding Cake”. As an internee transport ship she was painted gunmetal grey and her ribbons removed. Fencing was used to separate the decks and barbed wire entanglements covered possible escape routes. A cannon was mounted on her stern to counter aircraft fire. However, some of the features of her-pre war use remained, such as the mirrors in the ball room. On 30 June 1940, without escort, she set sail from Liverpool docks under the command of Captain Edgar Wallace Moulton.

Two days later, on 2 July 1940 at 6.30am, The Arandora Star was torpedoed 125 miles West of Ireland by the German U Boat, U47, under the command of Gunther Prien. It took thirty-five minutes for the Arandora Star to sink. 841 people died.

446 Italians internees

243 German and Austrian internees

42 crew

97 military guards

12 officers

Captain Edgar Wallace Moulton

What happened to the 586 survivors?

250 or so Italian survivors were taken to Greenock, Scotland. 50 badly injured individuals were taken to hospital and later to internment camps on the Isle of Man. However, 200 internees who were fit to travel were 8 days later boarded the SS “Dunera” bound for Australia where they would be interned for five years.

Was the sinking of the SS “Arandora Star” made public?

On 04 July 1940 the Daily Telegraph reported the sinking on the front page. The high loss of life was attributed to panic among German and Italian internees and a fight for lifeboats heavily increased the death toll hampering British rescue efforts. However, years later it would emerge that there were many other reasons for the large loss of life. The ship carried 1673 men, around one thousand passengers over her normal capacity with life-jackets and life-boats enough for a third of the people on board. Those who were able to get to the life-boats first had to circumnavigate fences with barbed wire entanglements to get to the decks. Only seven out of twelve life boats were launched successfully. Those who were able to access the few available life jackets leapt into the water from too great a height, instantly breaking their necks.

As the ship continued to list, the covered mirrors that surrounded the ballroom fell smashing onto the passengers below causing more horrific injuries. There were sons who would not abandon their injured fathers - many passengers could not swim. As the ship began to list even more, the cannon on the stern broke its mooring dragging down the barbed wire, which in turn dragged down all the men clinging onto the ship.

What was the reaction by the British government when they learned of the SS “Arandora Star”?

In November 1940 an independent enquiry conducted by Lord Snell investigated the selection method of Italian aliens sent overseas in The Arandora Star. Amongst the concluding points he found that: ‘The lists were largely based on membership of the Fascist party, which was the only evidence against many of these persons’. The result was that among those deported were ‘a number of men whose sympathies were wholly with this country’. However, he concluded that in compiling the embarkation lists of Italians it seems likely that errors occurred in about a dozen cases. Taking the broad view of the programme of deportation and the conditions under which the work of selection had to be done, Lord Snell did not consider this number of errors a cause for serious criticism.

Harold Farquhar, an overseas diplomat at the Foreign Office, involved in the Arandora Star and its aftermath greeted Snell’s report with dismay. ‘The whitewash has been laid on very thick,’ wrote Farquhar

Who were some of the victims of the tragedy?

Padre Gaetano Fracassi from Manchester. He was 64 years of age and had dedicated his life to the Manchester Italian community. Gaetano Pacitto, a naturalized British subject from Hull, 65 years of age. Francesco D’Ambrosio, confectioner and restaurateur from Hamilton, had applied for naturalization and had two sons serving in the British Army. He was also the oldest Italian, born in Picinisco, high in the Abruzzi Mountains in 1872; he was 68 years of age. Decio Anzani from London. He had lived in Britain for 31 years and was the secretary to the anti-Fascist organization, the League for the Rights of Man.

Did the British government offer compensation to the families of the victims?

Claims for compensation were made by some relatives only to be rejected by the Secretary of State. This was because The Arandora Star had been sunk on the high seas by an enemy torpedo without warning, contrary to well recognized rules of warfare and his Majesty’s government could not admit the principle of paying compensation in respect on interned aliens who lost their lives through ‘the barbarous act of an enemy government’.

What impact did internment and the sinking of the SS “Arandora Star” have after the war on the Italians resident in Britain?

The combined effects of xenophobia, destruction of property, arrests, deportation, and the sinking of The Arandora Star, were devastating for the Italian community, especially to the children who had grown up without their fathers either through internment or death. Tainted by the experience many internalized their Italian identity anglicizing their names, refusing to speak or learn Italian and to become invisible. Many children who lost their fathers were never given the time to mourn, as Graziella Feraboli a 14 year old girl living in London at the time when she lost her father Ettore on The Arandora Star said, “and then came the Blitz”

Research by Stefano Paolini.

Sources include material by Terri Colpi, Maria Serena Balestracci and Lucio Sponza.